Swift Technological Progress Of

PHOTO CHEMICAL MACHINING — A BRIEF PROCESS HISTORY

The development of knowledge of acid attack upon metals is not new, its origins lie in antiquity. Legend tells that the ancient Greeks had discovered a fluid, which is referred to as liquid fire, that attacked both inorganic and organic materials. However as this was the Bronze age it is unlikely that they possessed the technology to manufacture such an acidic chemical. The ancient Egyptians etched copper jewellery with citric acid as long ago as 2500BC. The Hohokam people, of what is now Arizona, etched snail shell jewellery with fermented cactus juice around 1000BC.

Chemical etching was not used regularly in Europe until the fifteenth century when it was used to decorate suits f armour. Engraving was impossible since armour was forged as hard as the chisels of the day. The earliest reference to this process describes an etchant made from common salt, vinegar and charcoal acting through a hand scribed mask of linseed oil paint. Decorative patterns where also etched into swords by means of scribed wax resist. These techniques were adapted and improved by etchers operating in close co-operation with armourers until, by the seventeenth century, armour had become wholly ceremonial and great works of etched art .

The sixteenth century saw the use of etching techniques to produce printing plates of a superior quality to those previously engraved. The main advantage being the lack of burrs During the mid seventeenth century etching was used for the indelible caalibration of measuring instruments and scales such as an artillery gunners conversion table etched around 1650. This related the bore of a cannon in relation to the weight of the shot and assisted in the estimation of its trajectory.

Two developments within the space of forty years in photography laid the foundations for the photoresists we use today. In 1782 John Senebier of Geneva investigated the property of certain resins to become insoluble in turpentine after exposure to sunlight.Inspired by this, Joseph Nicephore Niepce resurrected an ancient Egyptian embalming technique that involved the use of what is now known as Syrian asphalt. This hardens after exposure to several hours of sunlight, into an acid resistant film. However, it took constant experimentation until this development was a success in 1822. The result was a resist that could be photo-polymerised in the exposed areas whereas the unexposed areas could be developed off in a solution of oil of lavender in turpentine. The age of phto etching had arrived.

By 1925 the huge daily newspaper industry made large-scale use of printing plates etched in nitric acid.By 1927 the use of chemical milling through a rubberised paint mask, which was hand cut around a template, was being used as an engineering production tool.

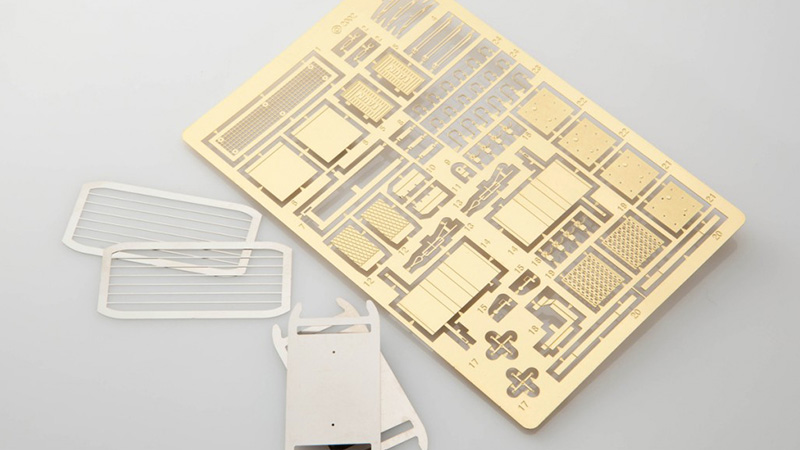

John Snellman may have been the first to produce flat metal components by photo chemical machining of shim stock that was too hard for punching. He innovated the use of cutting lines, or outlines, in the photoresist mask. This ensured even simultaneous etching of every component detail and also his use of tabs secured the parts into the parent metal sheet. He patented the process in 1944 whereafter it was increasingly used to manufacture shims, springs, stencils, screens and virtually any complex shape which for technical reasons could not be punched. Within ten years two American companies, the Texas Nameplate Company and the Chance-Vought Aircraft Corporation had taken a considerably refined Snellmans process and renamed it Chemi-Cut.

The photo chemical machining process was further developed on both sides of the Atlantic, becoming a production process in the UK in the early 1960s. Development was further accelerated by the introduction in commercial applications of the printed circuit board. The high volumes required for this product saw large strides in development, particularly in the design of etching equipment. These improvements quickly transferred to the photo chemical machining process, leading to the industry we see today.

The sixteenth century saw the use of etching techniques to produce printing plates of a superior quality to those previously engraved. The main advantage being the lack of burrs During the mid seventeenth century etching was used for the indelible caalibration of measuring instruments and scales such as an artillery gunners conversion table etched around 1650. This related the bore of a cannon in relation to the weight of the shot and assisted in the estimation of its trajectory.

Two developments within the space of forty years in photography laid the foundations for the photoresists we use today. In 1782 John Senebier of Geneva investigated the property of certain resins to become insoluble in turpentine after exposure to sunlight.Inspired by this, Joseph Nicephore Niepce resurrected an ancient Egyptian embalming technique that involved the use of what is now known as Syrian asphalt. This hardens after exposure to several hours of sunlight, into an acid resistant film. However, it took constant experimentation until this development was a success in 1822. The result was a resist that could be photo-polymerised in the exposed areas whereas the unexposed areas could be developed off in a solution of oil of lavender in turpentine. The age of phto etching had arrived.

By 1925 the huge daily newspaper industry made large-scale use of printing plates etched in nitric acid.By 1927 the use of chemical milling through a rubberised paint mask, which was hand cut around a template, was being used as an engineering production tool.

John Snellman may have been the first to produce flat metal components by photo chemical machining of shim stock that was too hard for punching. He innovated the use of cutting lines, or outlines, in the photoresist mask. This ensured even simultaneous etching of every component detail and also his use of tabs secured the parts into the parent metal sheet. He patented the process in 1944 whereafter it was increasingly used to manufacture shims, springs, stencils, screens and virtually any complex shape which for technical reasons could not be punched. Within ten years two American companies, the Texas Nameplate Company and the Chance-Vought Aircraft Corporation had taken a considerably refined Snellmans process and renamed it Chemi-Cut.

The photo chemical machining process was further developed on both sides of the Atlantic, becoming a production process in the UK in the early 1960s. Development was further accelerated by the introduction in commercial applications of the printed circuit board. The high volumes required for this product saw large strides in development, particularly in the design of etching equipment. These improvements quickly transferred to the photo chemical machining process, leading to the industry we see today.

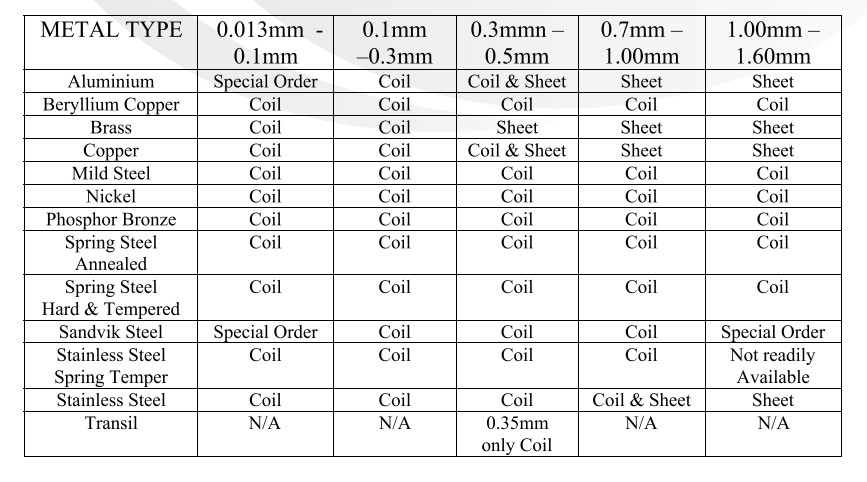

METALS SUITABLE FOR THE ETCHING PROCESS

METAL TYPES

Most metal are suitable for the etching process. The method of production and the chemical composition both have a bearing on the rate of processing,the overall finished size, tolerance and the appearance of the etched edges.Some alloyed materials do cause particular problems to the process e.g. a high carbon content contaminates the etching chemicals unless filtered out at the processing stage(refer to therate of etch). Silicon causes particular problems with both the etching rate and adhesion of the photoresist to the surface of the material (refer to metal preparation).Metals that have an alloying content of Cobalt, Palladium or Titanium have to be given careful consideration. These three alloys especially can be a major factor in preventing a successful etch. Alternative etching chemistry can be used to etch Titanium. However, as most commercial etching machines use Titanium for the metallic components within, a successful Titanium etch equates to a wrecked machine. Precious metals can be successfully processed, but as special chemistry is required most commercial etching companies do not process these metal types unless the volume is high enough to warrant the special conditions. The majority of metal processed is cold rolled stock. However, sintered metals such as Molybdenum can be successfully processed. Pre-plated materials are generally not processed as the etch rate of the plating metal will differ from the base metal. This could consequently cause tolerance problems and cut back the plated finish to unacceptable levels.Consequently plated components are etched and post plated.

TYPICAL MILL STOCK